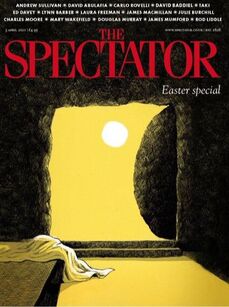

The empty tomb is not a metaphor as much as it is an event recorded in history within the sacred text of the Bible; that the Spectator should feature the image on the front cover of its Easter edition is testament to its enduring message in the midst of secular society. The cover presides over the article ‘On the Rise of Spiritual Consumerism’ written by James Mumford brother of Marcus who is lead singer of the band Mumford and Sons. The brother’s parents John and Ellie Mumford are founders of the UK Vineyard Church Movement and it is from this up bringing that James draws on his Easter piece. Mumford writes about his early days in the Vineyard and how they drew on the distinction between spirituality - the vogue term around which his church experience appealed, and religion - a word assigned to be forgotten and lost to history. Latterly he has changed his position to establish the place of religion in life by pointing to the fact that transformation is an arduous rather than glitzy affair. 'There is a beautiful banality about belonging to a particular community.' he writes, 'Nothing could be less sexy than the Bible study I ran with my wife Holly for our local Anglican church. But because the people who came were committed to it - turning up week after week - what started out as an awkward and disparate group of strangers of all different ages and backgrounds morphed over time into a diverse community where people slowly started to feel they belonged. What happened there was not dramatic, but it was profound.' In truth I think at its best this is what religion does - it creates community out of disparity - a coming together around a creed, a confession - and the Christ. What happens in that setting of ordinariness is the formation for which each soul searches - community and connection. I used to see this all the time pre-Covid, how a small group here and a gathering there become life lines of community and hope - and oh, how its needed. Recent statistics for the UK saw 8% of adults who were "always or often lonely" - representing 4.2 million people. That phone call you make, card you send or meal you cook become the real life lines - it is here in the nitty gritty of every day life when in the midst of your own busyness you extend a hand to another that the work of true religion takes place. As the apostle James wrote: ' Religion that God our Father accepts as pure and faultless is this: to look after orphans and widows in their distress and to keep oneself from being polluted by the world. (James 1:27)' In my earlier years I would have been amongst those happy to lose my religion and wear its ousting as a badge of honour - those fine young radicals who would have burned the hymn books and consigned liturgy to history as we forged ahead with the spirituality of the modern age. Now I am not so sure. Turning up week after week - saying my prayers, offering juice to my lips and entering conversations in a community of diverse people feels quite other worldly. When we gathered in person for the first time for a long time over the Easter weekend the whole encounter felt an emotional affair. As if it were meant to be that way - forgiving those who offend me, extending grace to those who pass by, taking time to endorse the stories of people I otherwise would never meet. This is religion - not the latest trend to capture the market but a collision at the old rugged cross where, if I stay long enough - and come back time and again, my life will be slowly and irreversibly changed. It's an odd thing is religion - but one is left to ponder whether it might still present itself as being the foundation to inner contentment and community flourishing and losing it is, perhaps, best avoided.

0 Comments

|

Author

Archives

December 2022

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed